A journey through the religious imagination of the Jörai people

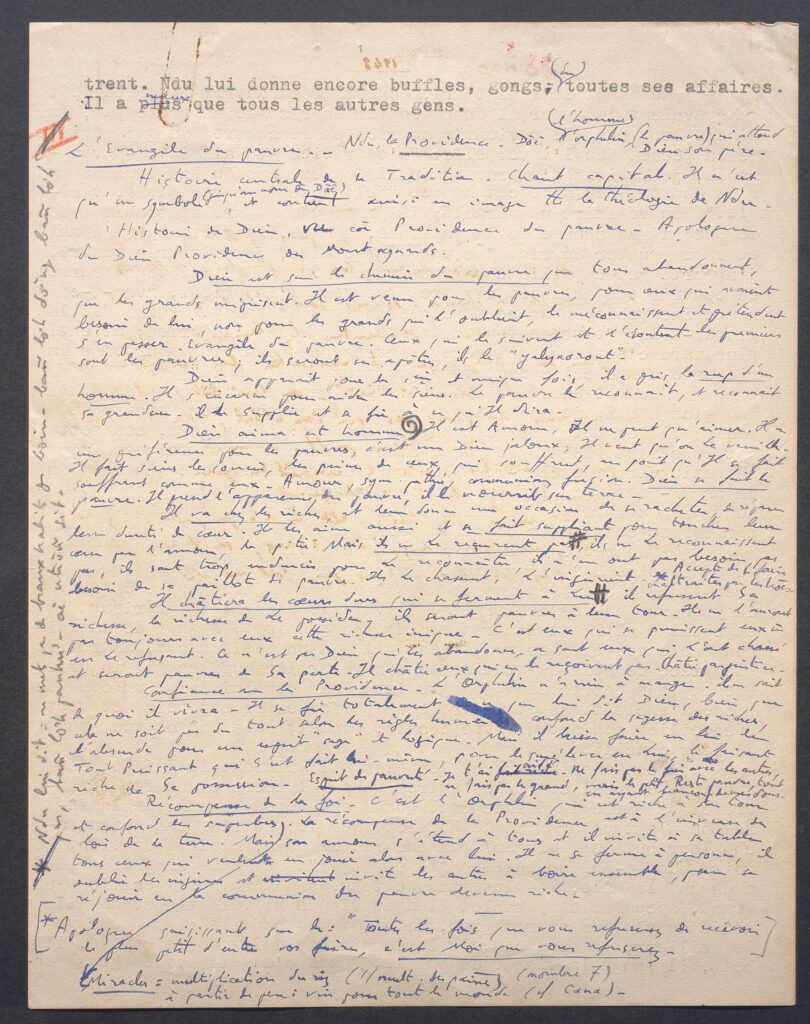

The young Father Dournes quickly attributed the relative failure of his apostolate to his lack of understanding of the Jörai’s religiosity. We must try to embrace their way of thinking, to the point of almost finding that their religion is not so bad! he wrote provocatively to his colleagues, justifying his desire to penetrate the religious soul of the Jörai. The task would have been impossible for a visiting ethnologist: a population tends to hide its soul. With time and linguistic ease, Dournes was able to penetrate their innermost thoughts, understand and categorize Jörai religious practices.

“I learned as much about their religion by watching how they planted rice or how they dyed cotton skeins with indigo. Because all of that is also linked to religious rituals.”

Hence the observation that the Jörai religious imagination, like its ecology, is based on a system of relationships between the elements of the universe. Religious expression is thus the search for order, for a permanent balance between these elements. These sacred relationships are personified in the yang, present everywhere in the cosmos and the material elements. The purpose of rituals and sacrifices is to ensure that the beneficial yang remain favorable and that the malevolent yang break their harmful ties with humans.

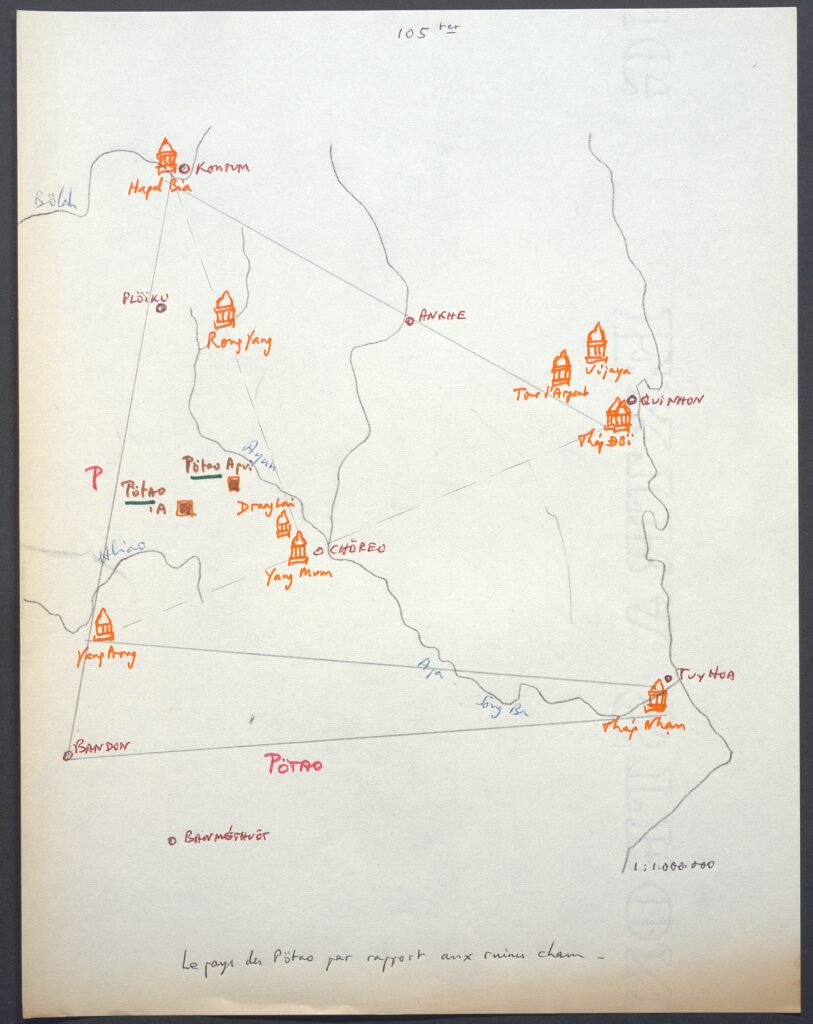

The guardians of this cosmic order are the Pötao, known as Master Fire, Master Water, and Master Air, the political heirs of the ancient Jörai kings. For fifteen years, Dournes managed to rub shoulders with these mysterious figures, who straddle the temporal and spiritual worlds, and to record their rituals, without knowing that he would later devote his doctoral thesis to them. What Dournes was the first to grasp were the religious functions of the Pötao, guardians of sacred objects that give them power over the elements.

Rituals

O YANG, HERE IS BEER AND PORK!

Benefits and curses

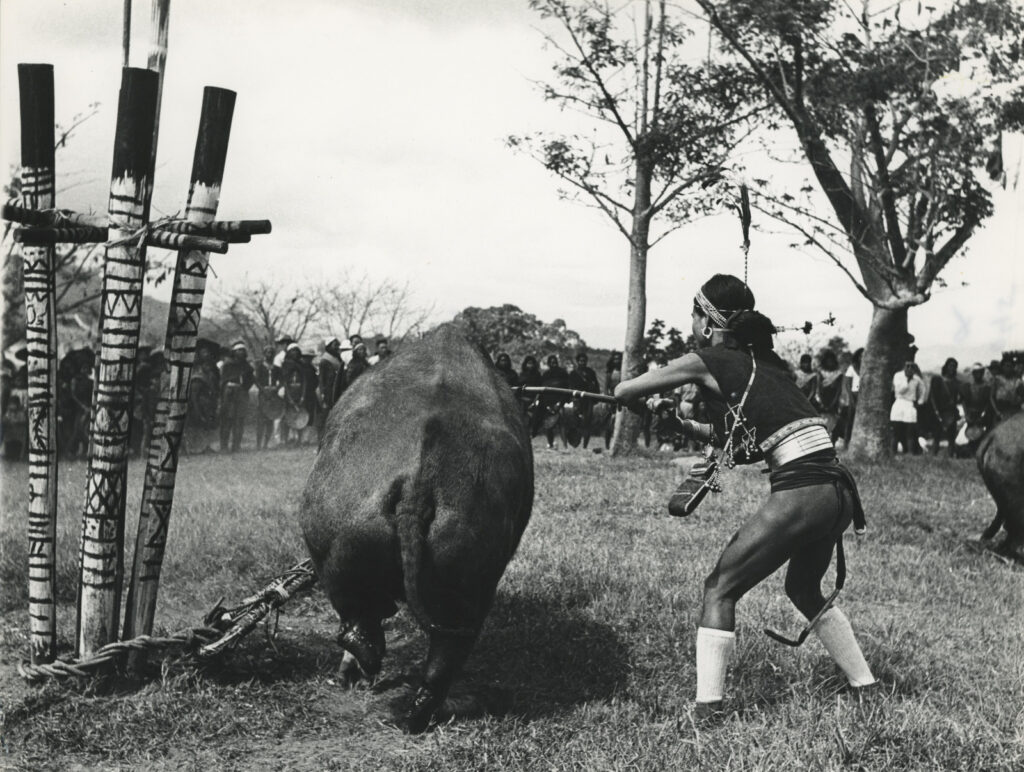

Benefits and curses are the forces that justify talismans, the reading of omens, and above all the tireless repetition of rituals and sacrifices in everyday life in Jörai. Dournes notes that a single family can sacrifice a new animal every day for a week if the shaman orders it. The sacrifice involves the bloody offering of a domestic animal, such as a chicken, pig, or buffalo, a precious victim raised in the village for the most spectacular sacrifices.

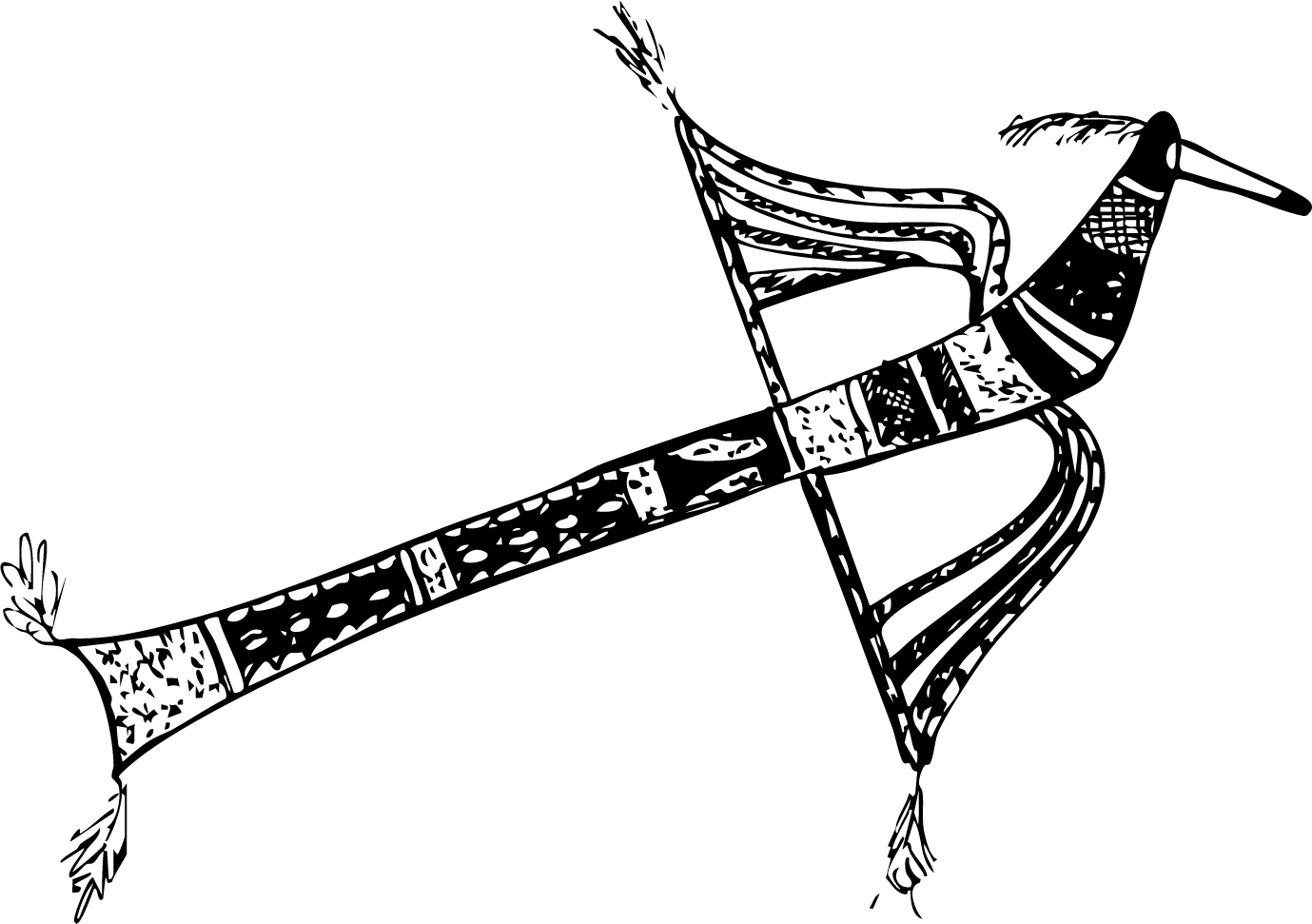

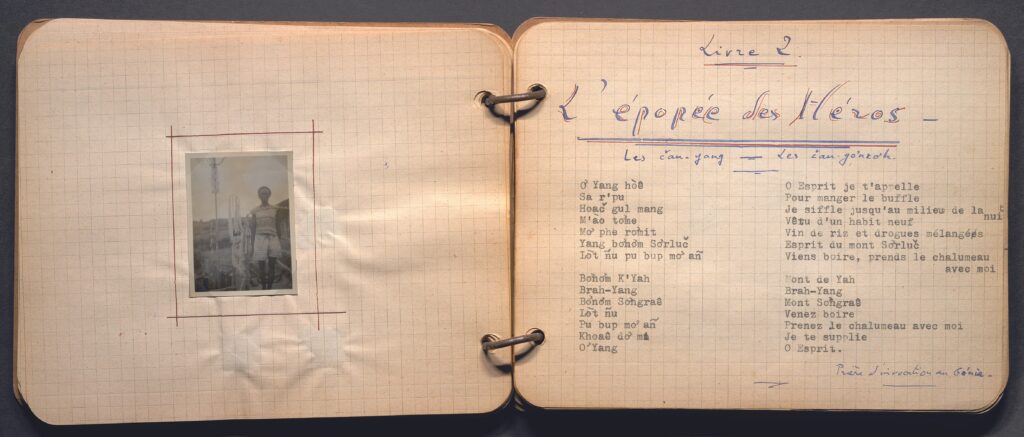

While the sacrifice is occasional, the ritual is present in every action, whether agricultural, domestic, military, or funerary. It involves both formulas, invocatory words memorized by women and spoken by men, and gestures. The sound of drums, gongs, and other instruments punctuates liturgical activities, with the ulterior motive that it too may have magical powers.

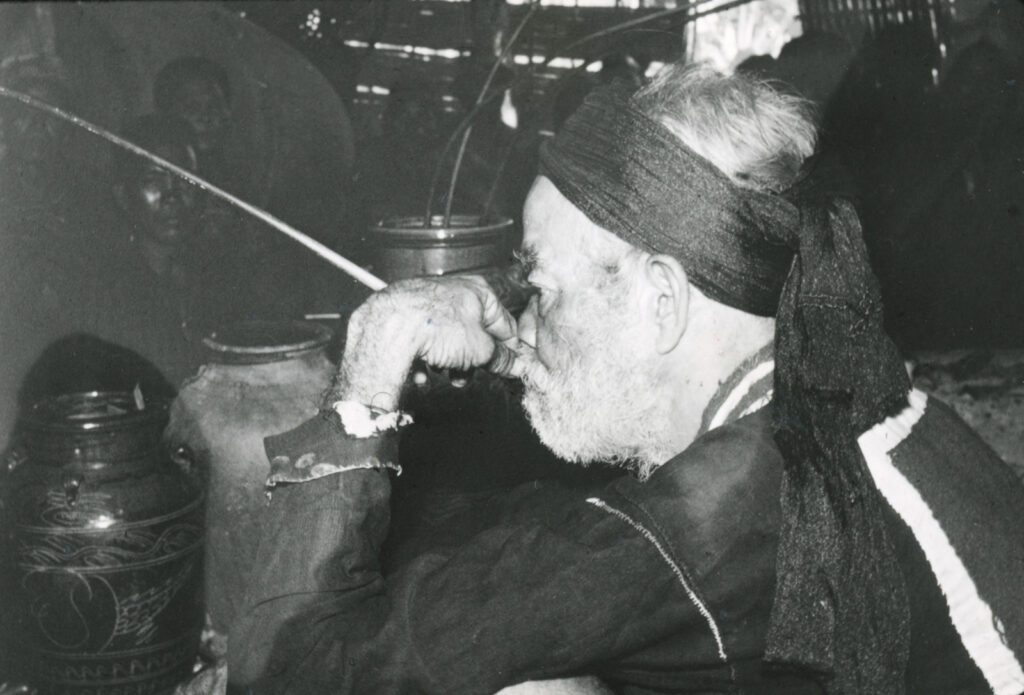

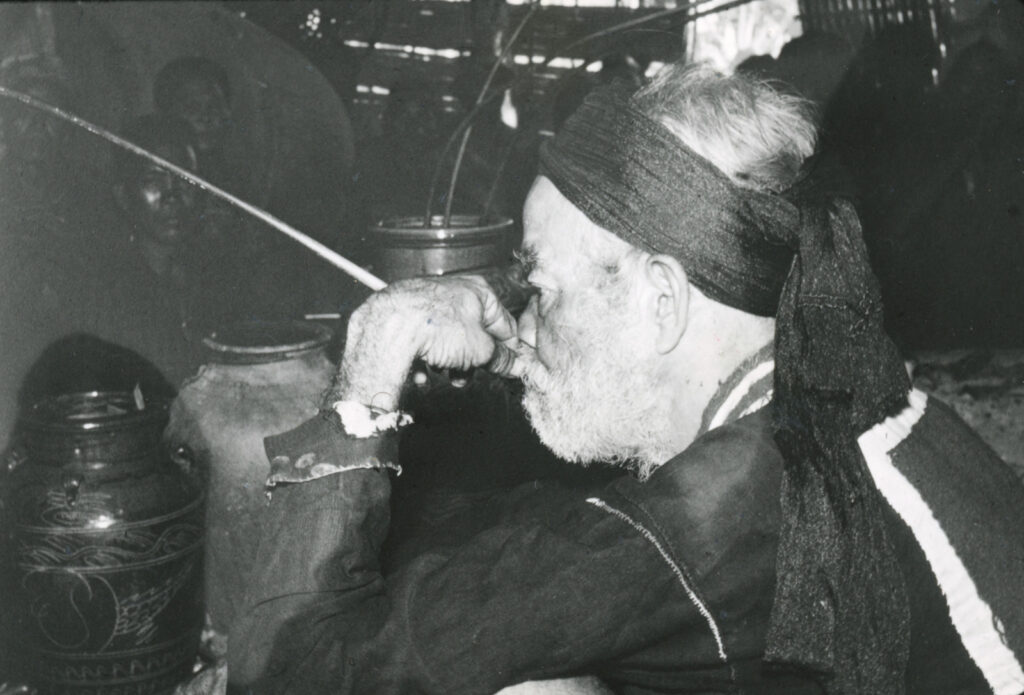

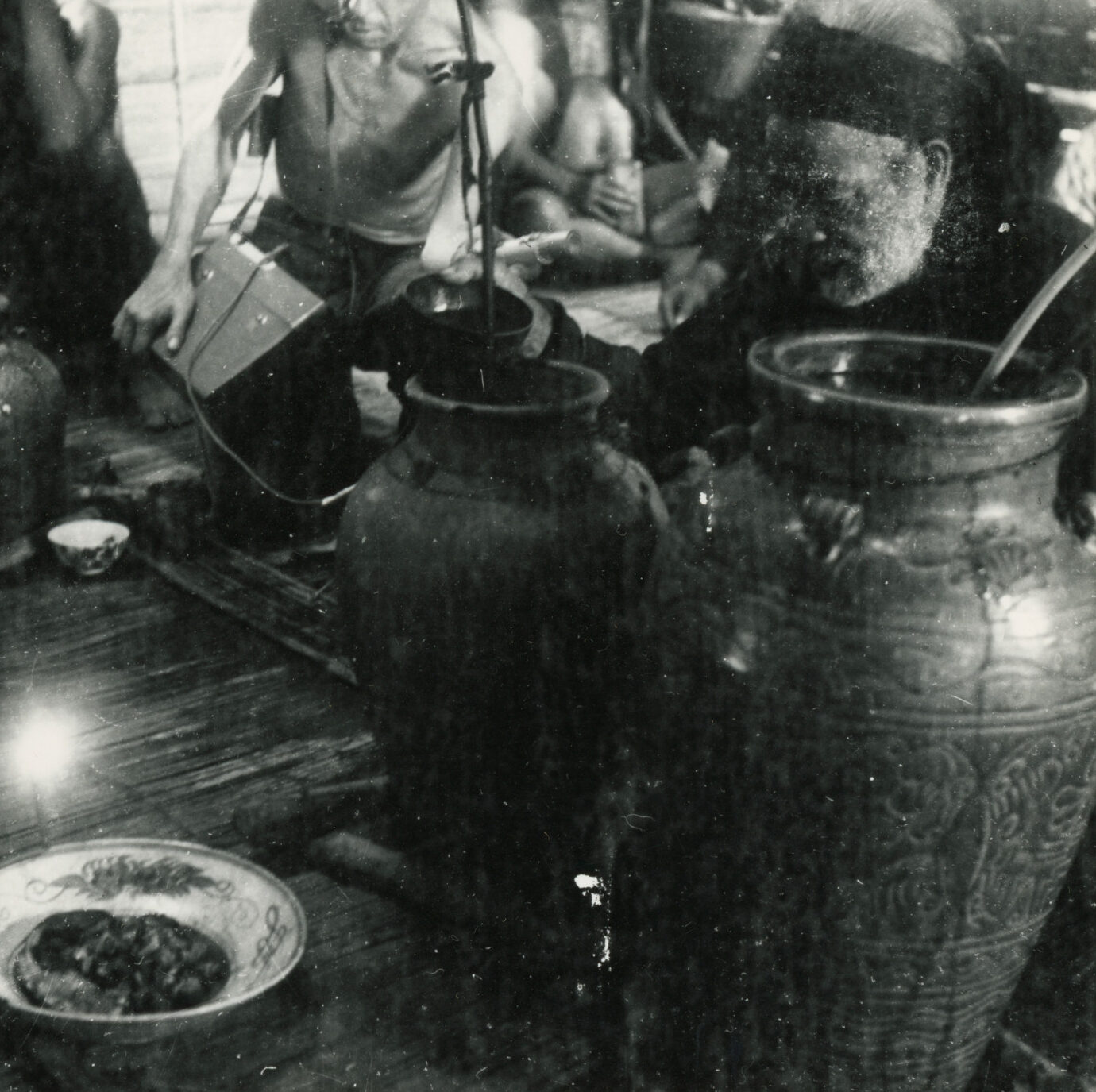

Rice beer

Another sacrificial offering poured as a libation is rice beer, flavored with narcotic plants. The yangs are invited to join the circle of drinkers around the jar and consume the soothing liquid through the bamboo straw reserved for them, to the sound of ritual chants.

Mythology, music: preserving oral tradition

The two arts truly practiced by the Jörai: Mythology – Music

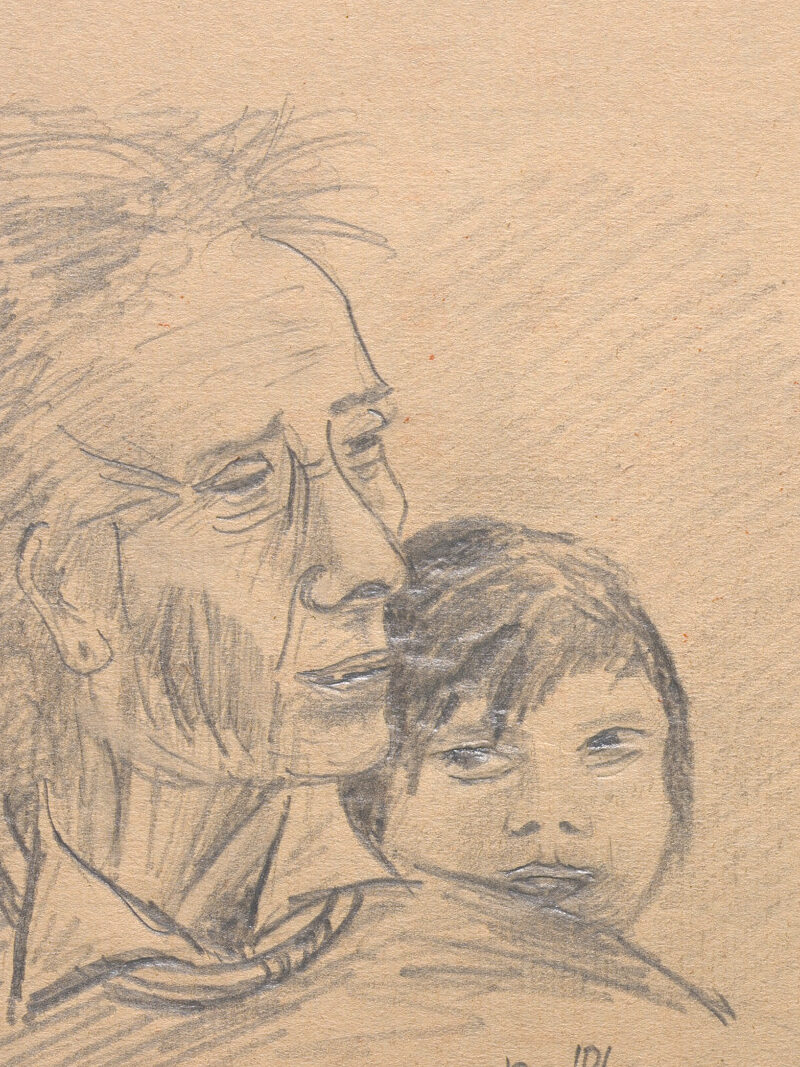

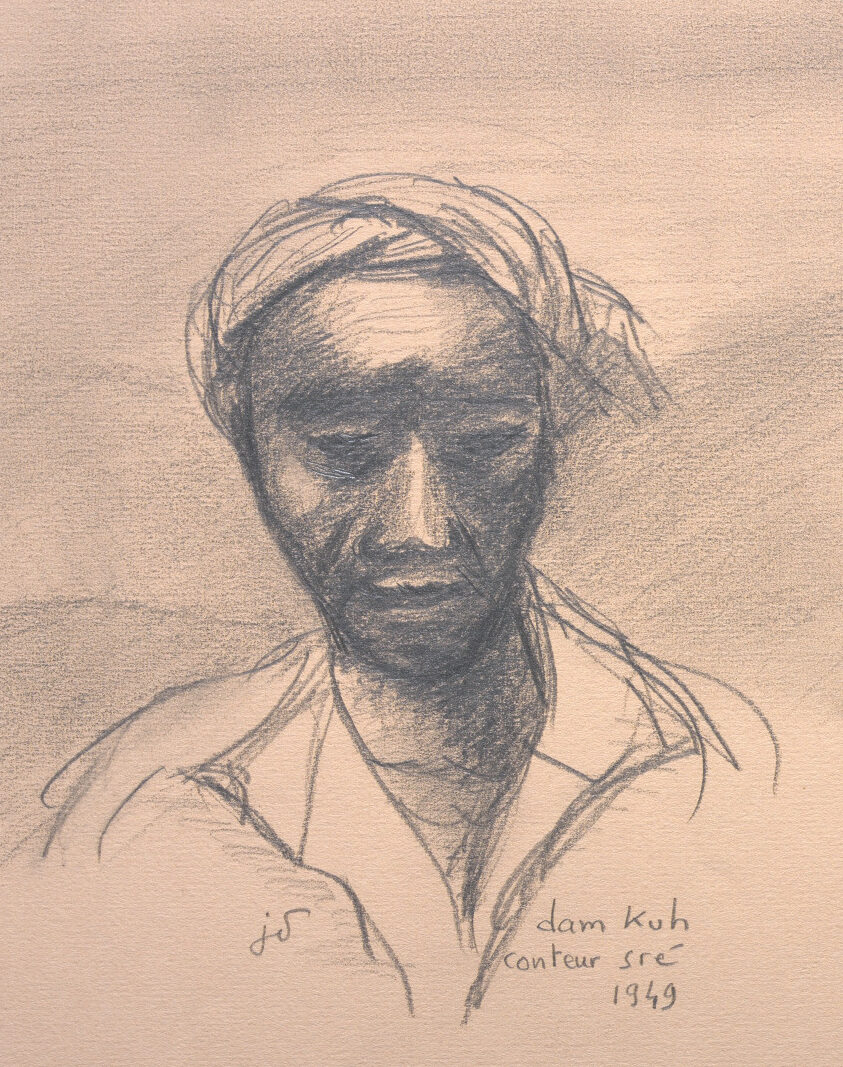

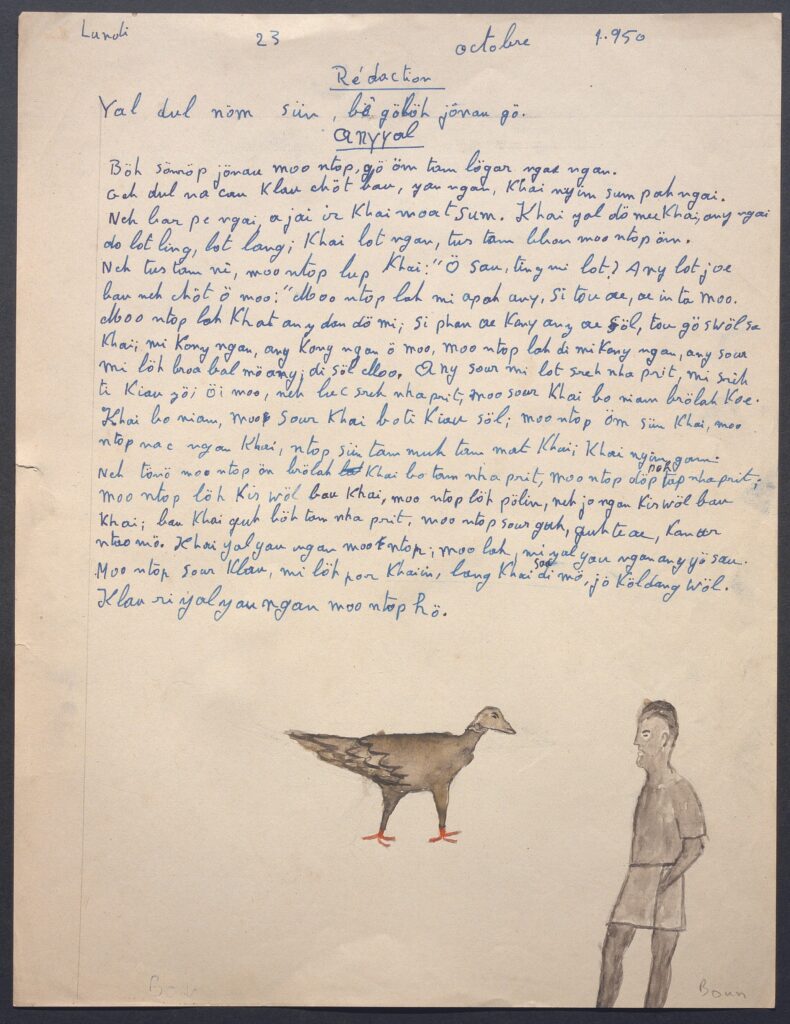

In the evening, around the jar, it is not only rituals that resonate; words prolong them. In the smoke of green tobacco, the storyteller unfolds myths, akhan, epics that convey the legendary universe of a people. Dournes eagerly seized upon these stories heard during evening gatherings as indispensable keys to ethnological understanding. To obtain spontaneity rather than provocation, and to gain acceptance for the use of a tape recorder, he had to win the friendship of the best storytellers. To transcribe and translate, he enlisted the help of the most educated villagers, so that the ethnography subject became an ethnographer. Once Dournes returned to France, some Jörai continued to send him myths transcribed by themselves.

As long as oral literature remains alive, the ethnic group remains true to itself. You can see naked children herding buffalo and holding a transistor radio to their ears, you can see young people revving up Japanese motorcycles, and in the evening you can find them listening to myths.

To study the entire oral heritage, Dournes adds to the myths ritual formulas, sayings of justice pronounced to settle disputes, funeral lamentations and courts of love, proverbs that pepper everyday conversation, songs, and games. Indeed, these recitations, passed down by word of mouth from generation to generation using a mnemonic system, form the basis of Jörai culture.

With a corpus of 250 Sré and Joraï myths and a thousand pages of “sayings,” Dournes became a theorist of oral literature. Enriching, publishing, and analyzing this treasure trove occupied the last twenty years of his life. Beyond words, he was fascinated by the language of gestures and expressions, the pinnacle of human communication specific to the world of orality. Through this field of research, which was dearest to him, Dournes sought to find the fulfillment of humanity in the uniqueness of a culture: “I don’t record to collect, but to help people know who they are.”

Collections of objects, photographs, and recordings, the fruit of patient fieldwork, situated within a living cultural context, can awaken our sense of relativity, help us avoid the ethnocentric criteria of those who make value judgments, and warn us of the dangers of standardization and all forms of totalitarianism that destroy originality.