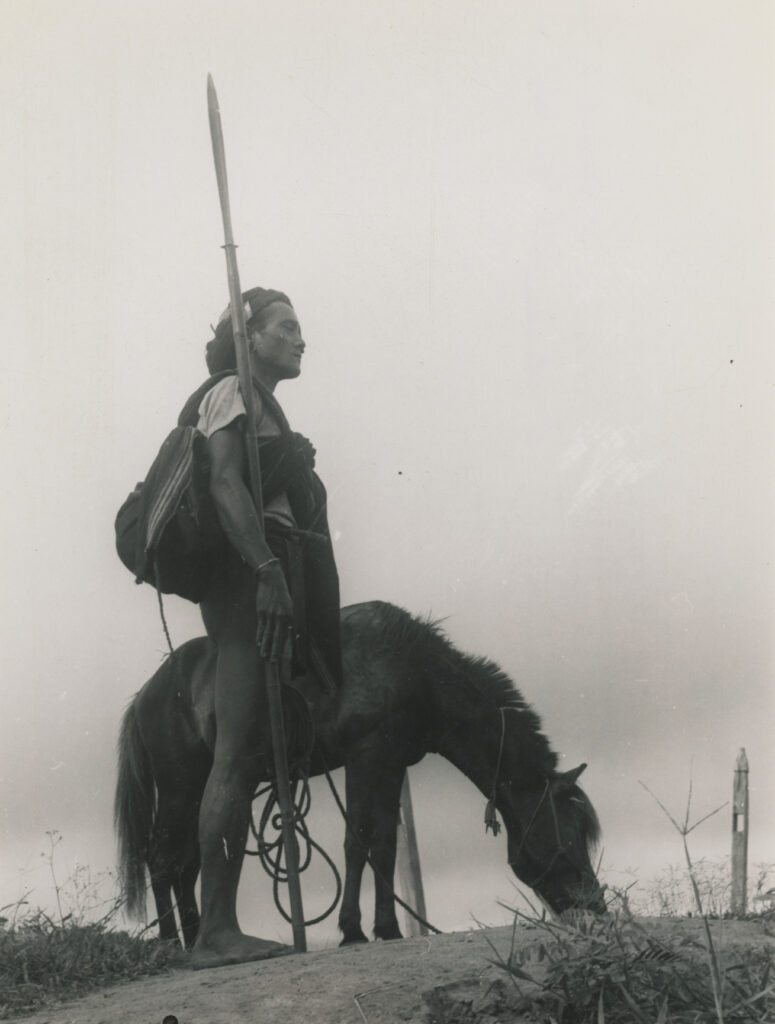

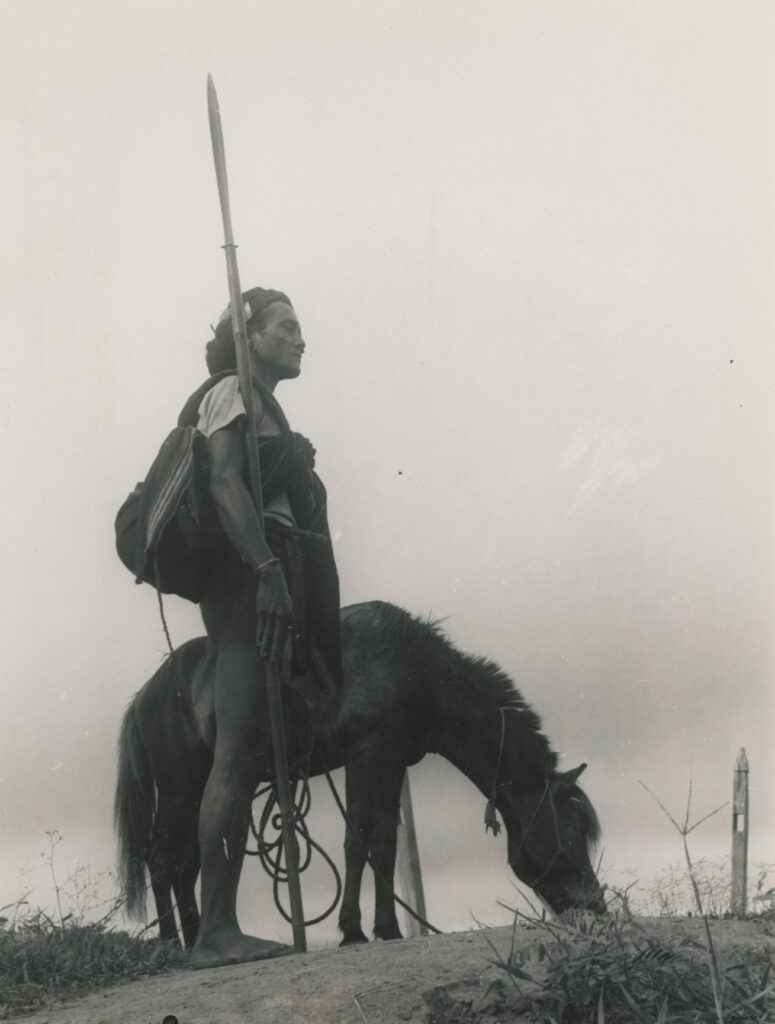

The forest stretches out around the village, a wild space necessary for life, a world that is both dangerous and attractive. The domain of men, while the village is that of women, the forest is home to hunters, woodcutters, and warriors. Very dense, it is crisscrossed by trails used by men to travel from village to village, quivers and crossbows on their backs. Dournes, whose apostolate extended over a hundred kilometers, immersed himself in the knowledge that the Mountain People have of their plant world as he traveled these trails. He notes that every Jörai can name a thousand plants, a sign of their constant interaction with nature.

Ethnobotanist

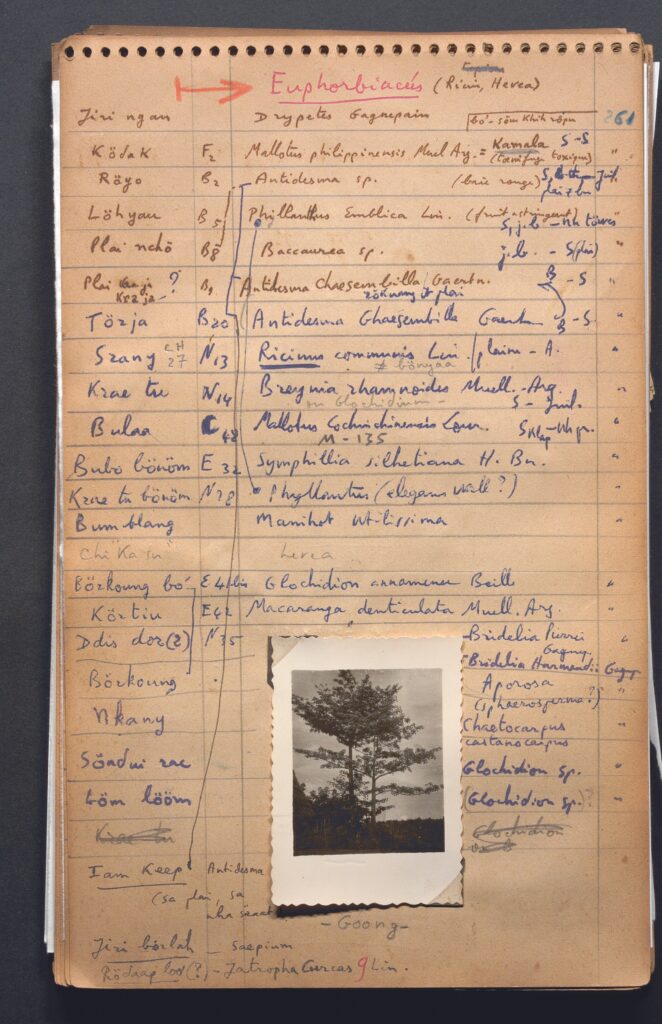

Dournes quickly refers to the heart of his scientific approach as “ethno-ecology,” which begins with botany and then describes the relationship between beings and their environment, through their own mental categories. He observes that, in the Joraï universe, each natural element is animated and enters into a relationship with its surroundings without opposition between human and non-human. Plants are in fact home to yang, sacred spirits, which are always evil when they come from the forest. In the forest, everything therefore bears the mark of the imagination and its ambiguity: we don’t really know if a civet is just a civet…

During the house-building rituals, this invocation is recited: Deity of the woods and bamboo, flee to another forest, to a distant land, do not remain here any longer!

Having witnessed the gradual destruction of the forests of the High Plateaux over two decades, under the successive blows of farming and bombardments, Dournes is trying to preserve them in his own way. He has created a “witness reserve” in one of the last islands of primitive forest, and cultivates the species he wishes to preserve in his garden. He often laments the endless consequences of deforestation, the decline in game, and the impoverishment of the soil. If the forest becomes desert, entire sections of the people’s very spirit disappear: it is the end of the world of their elsewhere, their dreams, and their myths. Don’t kill the forest, he says, or humanity would lose the living testimony of a harmonious society.

Bamboo wood, the plant aspect of the Jörai universe

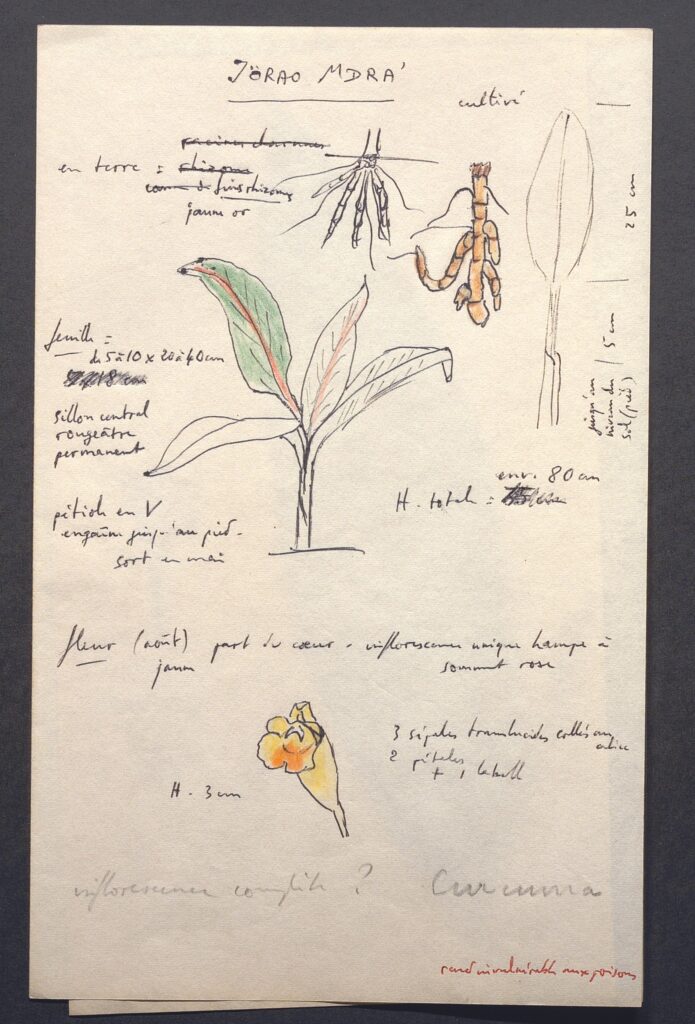

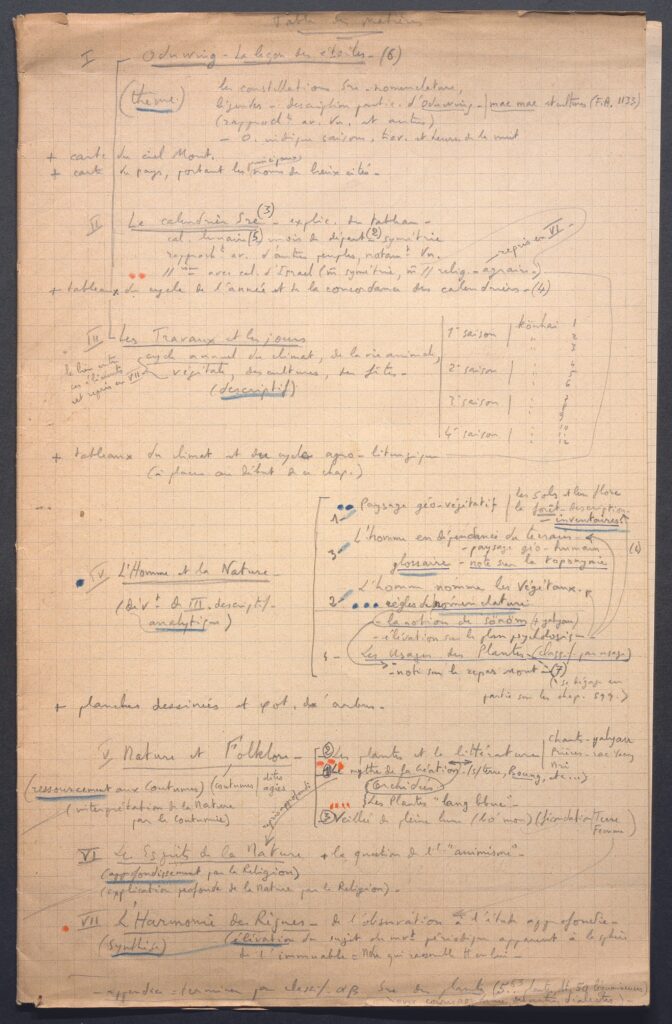

Bamboo wood, the plant aspect of the Jörai universe. This is the title Dournes gave to his first academic work, defended in 1968 after 20 years of botanical collection and analysis of the social and symbolic use of plants. Indeed, köyau-ale (or “bamboo wood”) is the double word used by the Jörai to refer to plants, especially in relation to humans.

Knowing plants to know people

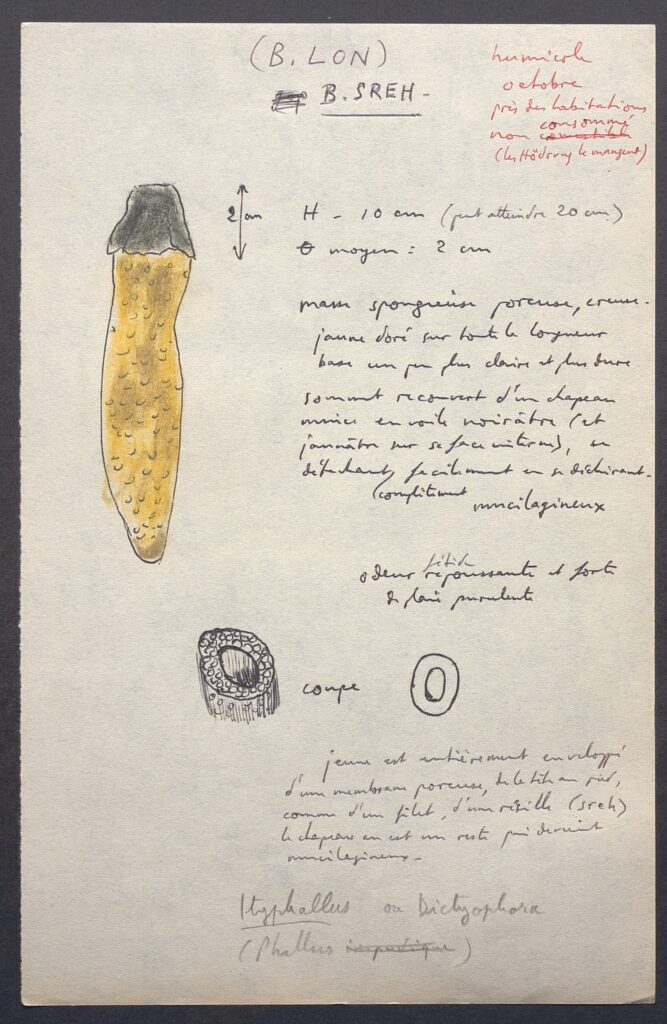

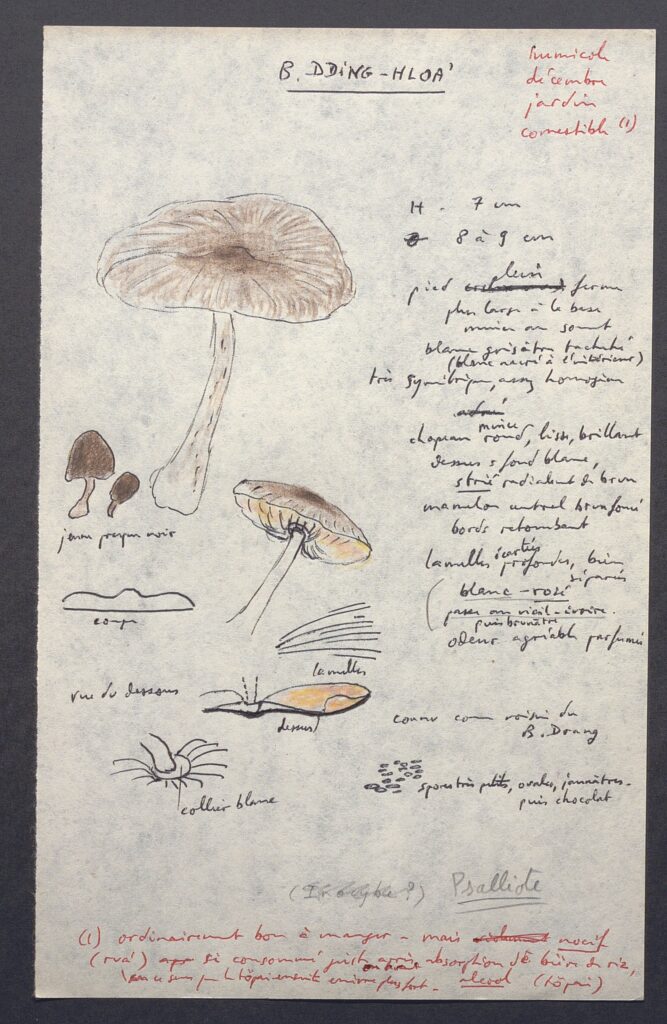

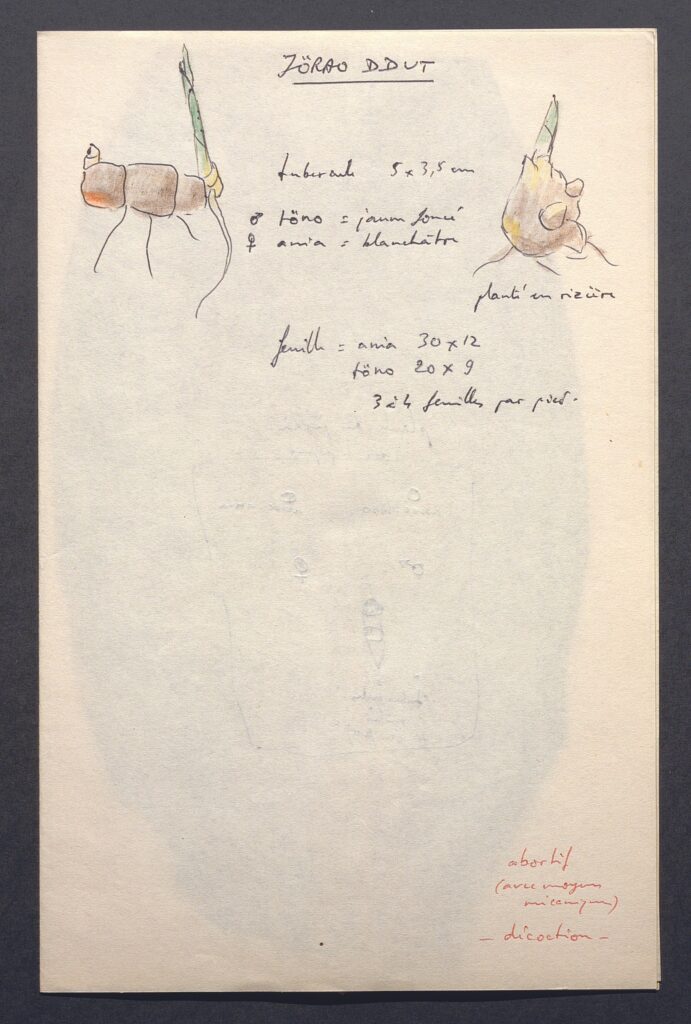

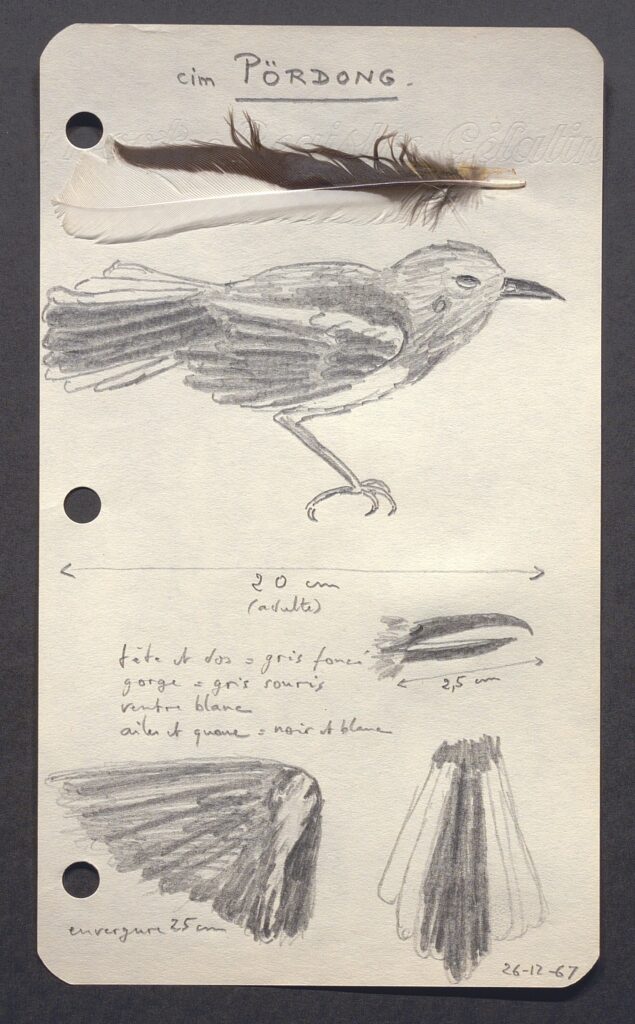

During his early years with the Sré people, like many of his fellow missionaries, Dournes collected plants and insects, compiled herbariums, and became a correspondent for the Natural History Museum to promote his findings. His hard work and desire to always dig deeper led him to focus particularly on ethnobotany, the way in which plants are named and categorized by different ethnic groups: Although I am interested in plants for their own sake, I see them primarily as an introduction to understanding people.

Life sciences

A “plant civilization”

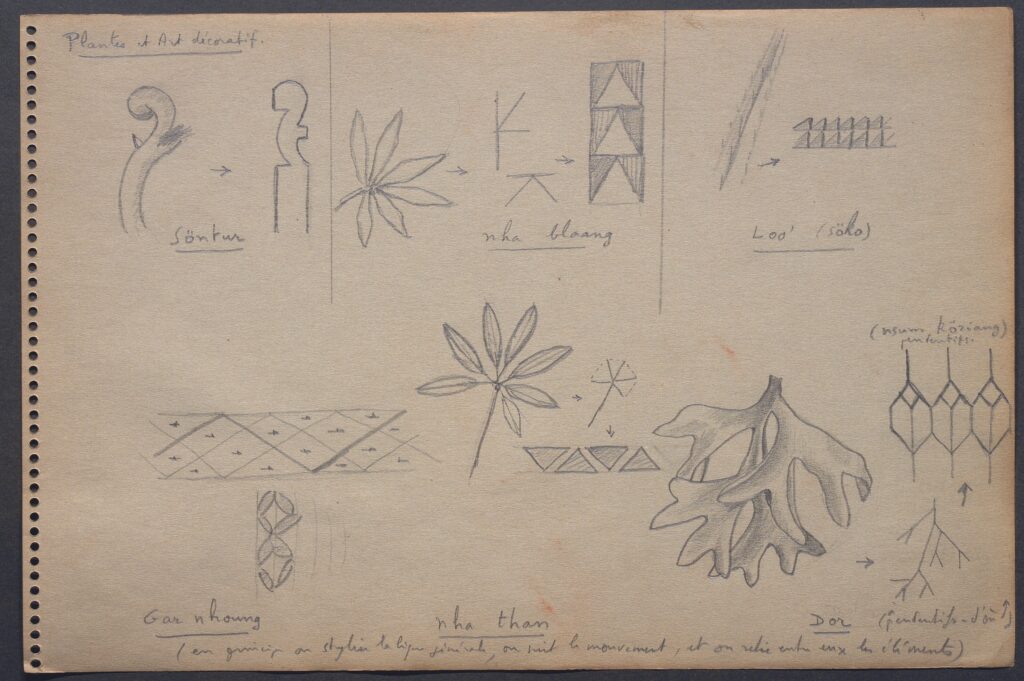

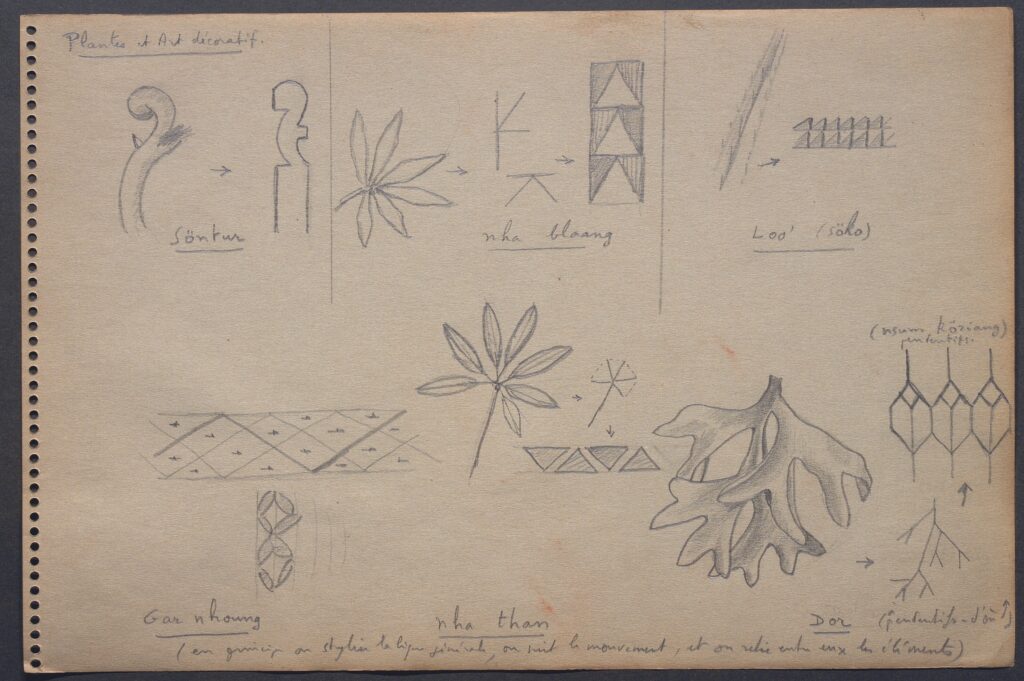

In his daily life at the heart of a “plant civilization,” he deciphers the modalities of the unique relationship between humans and plants. From a technical standpoint, he observes that leaves are the sole inspiration for basketry and weaving patterns. He describes at length the gastronomic, medicinal, and even shamanic uses of plants, as well as their literary appearances in myths and rituals: just as the banyan tree is the residence of superior and fertile spirits, the orchid also shelters particularly beneficial yang spirits.

War and hunting, two forest arts

A traditional art

From 1939 to 1970, Dournes experienced too much war. He therefore approaches this theme as a traditional art form rather than a history of conflict. Wars between villages and ethnic groups populate the mythical memory of the Jörai, valiant warriors and masters of skillfully codified shield movements. By the time Dournes encountered them, they had ceased these fierce rivalries, only to become victims of conflicts beyond their control.

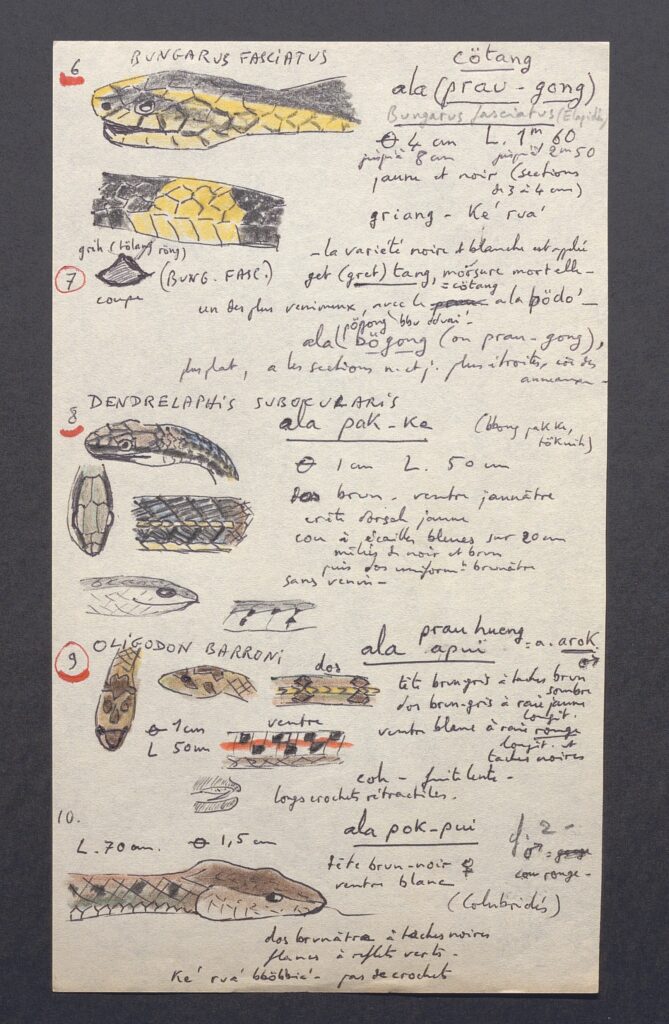

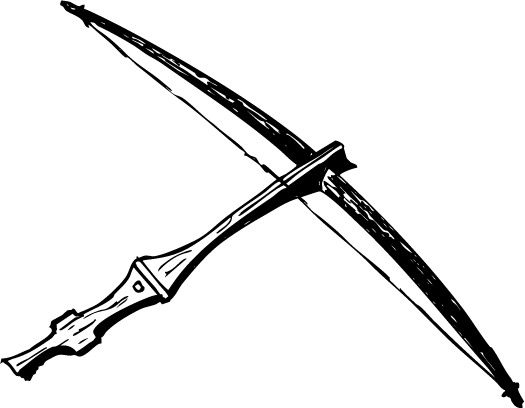

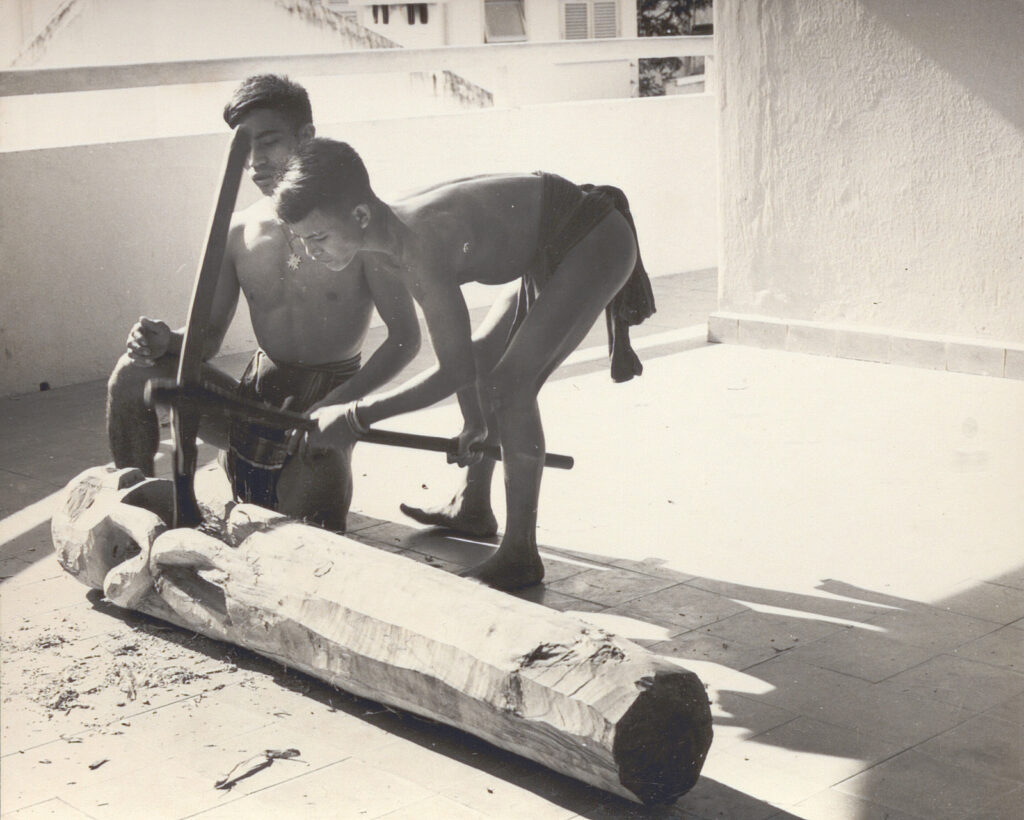

What Dournes observes are the practices of hunters. To catch large game (elephants, deer, wild boar, felines), they use the same type of equipment: woven quivers, bamboo arrows, and subtly assembled crossbows. The Jörai in the forest also demonstrate this ecology, a sign of the balance of the whole: when they cut down a tree, they ask for forgiveness, and when they kill a wild animal, they make a sacrifice of reparation.

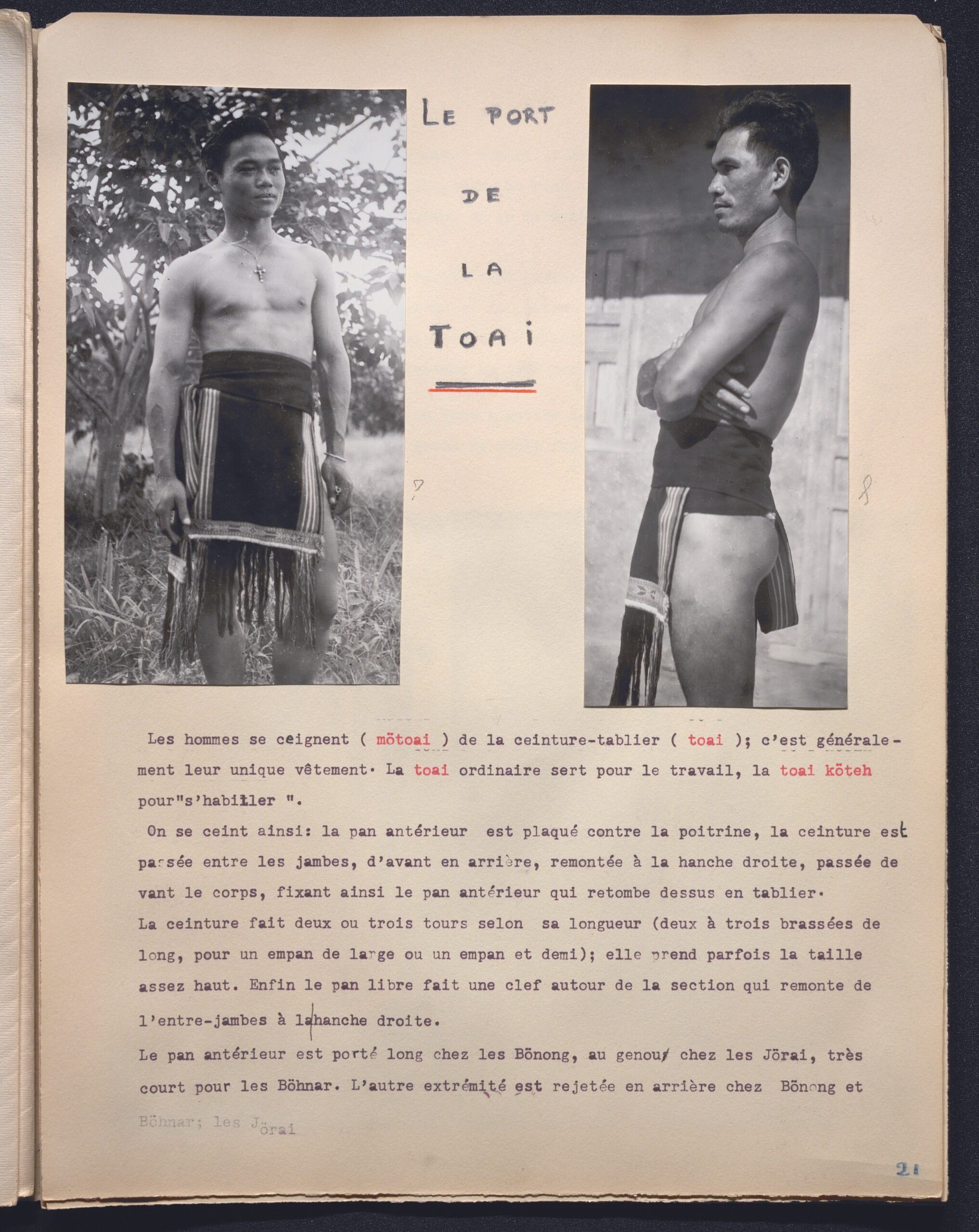

The “toai” or T-shaped belt

Wearing only a simple T-shaped belt, the man faces nature naked, without any adornments that would isolate him from his environment. His finely woven cotton belt, embroidered at the edges and elegantly draped, is in fact sufficient adornment for the elegance of the Jörai. It is this T-shaped belt that Dournes will wear exclusively at the end of his life in France.

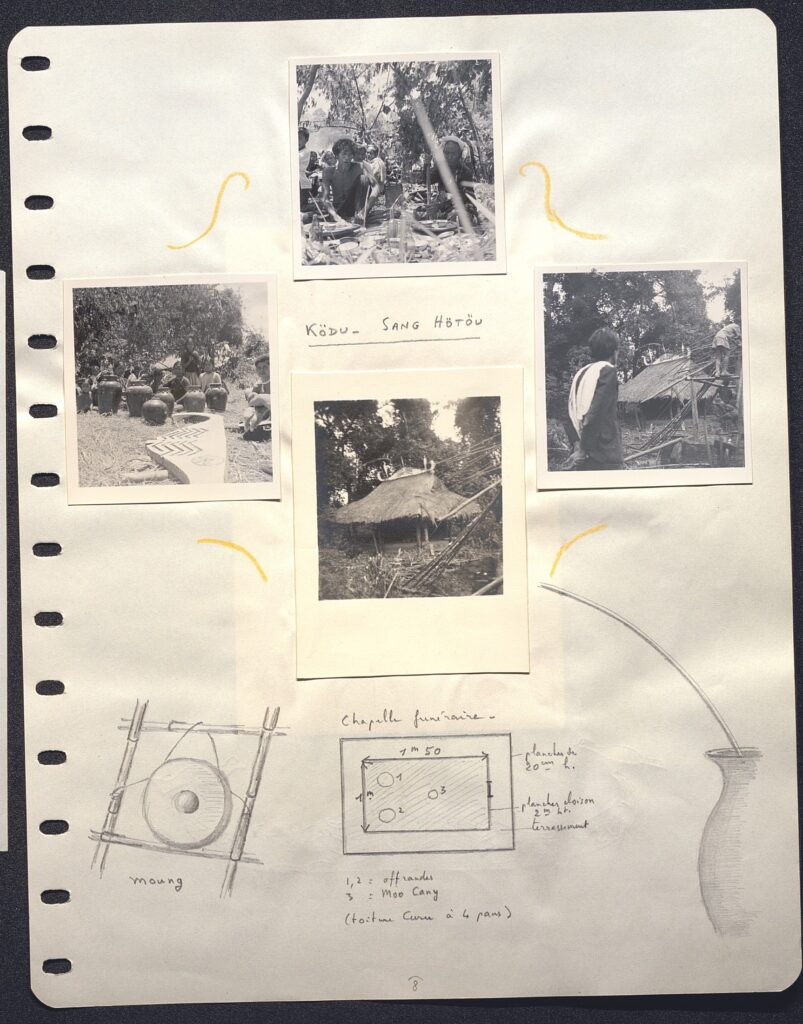

Between the forest and the village, the Pösat cemetery

I had a passion for cemeteries, for the sculptural treasures they contain.

The cemetery, an intermediate space

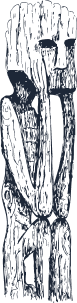

The edge of the forest: this is the space between dlei and bbon where the jörai burial ground is located. The cemetery is a veritable architectural complex, comprising tombs (pösat) and refreshment stands where the living gather. The palisade fence is topped with statues roughly carved from wood to represent those who accompany the deceased, mourners, or other human figures.

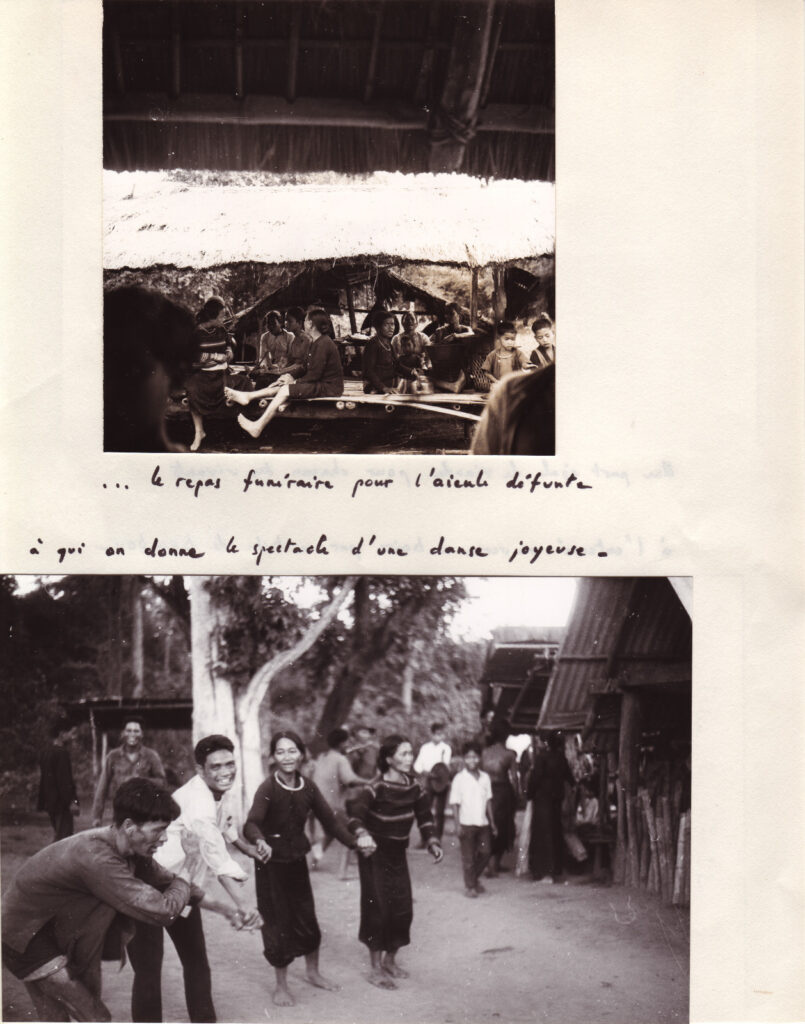

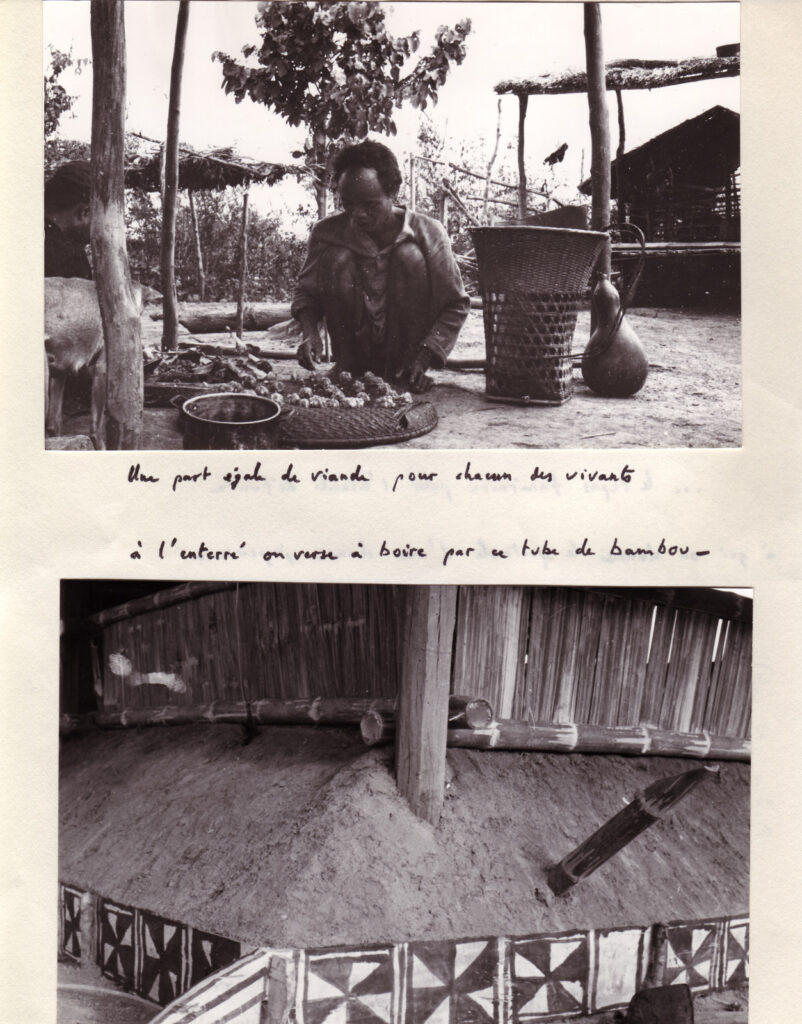

The cemetery is the setting for celebrations on the graves, extensively documented by Dournes in photos, texts, and sound recordings: extravagant decorations, carved and painted. At the cemetery, for three nights in a row, people drink and dance. It is the biggest spectacle the Jörai put on. The men offer beer and play gongs, while the women take the portion of meat to be offered to the deceased.

At the cemetery, three nights in a row, we drink and dance. It’s the biggest show the Jörai put on.

The deceased, abandoned in the forest

After a certain number of years, the deceased is considered to no longer be in their tomb but to have departed permanently for the afterlife. The pösat is then abandoned in the forest, so that the realm of the dead no longer interferes with that of the living. At the bend in a trail, under a canopy of vines, Dournes has often come across these abandoned funerary statues, whose patina evokes unique emotions.

The materials taken from the forest to build the house are plant-based and have yang energy (like everything else in this world), which means they have a sacred aspect, albeit a rather evil one in this case. As they will now become part of the human world (bbon and no longer dlei), they must be stripped of their sacred forest and clothed (for they cannot remain naked) in a sacred village, domestic yang, family yang—these, at least, we believe we know, whereas the yang of the forest… they have “charm” and can drive people mad. Man would do nothing without the forest, but he must not let himself be controlled by it.